Morning arrived and the previous night’s panic had gone the way of dreams. No doubt it really happened, but with the bright sun came the familiar feeling of safety – quite a change from nighttime stillness and my shadowy pursuer. The hotel now buzzed with inhabitants; I strolled down the hall to find the breakfast room a-chatter with Francophones – undoubtedly visitors to the university.

Having a proper English breakfast, I hit the revitalized sidewalks for my long-awaited day at the Bristol Record Office. The only way to know a city is to walk it streets, and in less than half a day of footwork, I had come to know a good portion of Bristol.

With a fresh start, I decided to give St Andrews another chance. It was on the way to the BRO and I would be crazy not to spend another hour giving each and every grave another go. This time, I entered from the opposite side – a narrow pathway arched over by leafless trees. Thin iron fences barricaded the cemetery from the public walkway, with carefree gates left open for a dog out walking its master, or the occasional curious wanderer.

I had to believe that the Admiral’s stature had influenced his final resting spot. There were numerous graves dated after 1863, therefore the people who laid my great-grandfather to rest had their options.

On a whim, I first revisited the east side of the cemetery. There was a dense matrix of graves whose orderly arrangement stood out from the rest of the haphazardly placed tombstones. I remembered searching it the day before, with stones ranging from tall and ostentatious to modest and flat. There was no real reason why I started there. Just a hunch.

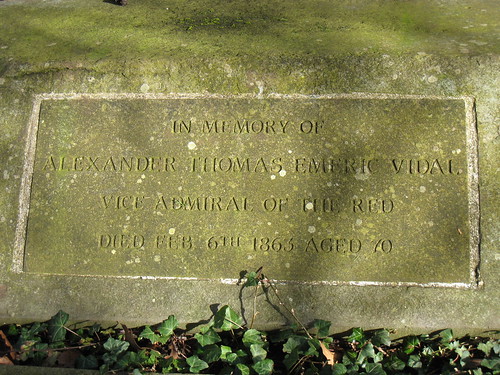

I approached the outermost row of graves, eyes scanning every stone in search of legible words and dates. And there it was -- modest and flat, the stone tinted green but otherwise in pristine condition. It was as if it had been patiently waiting for me all morning:

Serenity passed over me as I knelt to get a closer look. I found him! A man who lived an extraordinary life, hidden forever amongst the growing trees and fading stones of some forgotten corner of the world, far from family, far from home. In my imagination, it was akin to meeting a revered celebrity. My heart raced. I laughed out loud, impervious to the pedestrians who passed along the public pathway. A couple of drunken vagrants loitered nearby; no doubt I seemed madder than they.

While not a monumental challenge, it was a golden ancestral discovery. Here was the final resting spot of a man who went to sea at the age of ten; who mapped the Great Lakes while their neighbors were at war; who circled the African continent, meticulously charting its coasts and capes – a fragment of which still bears his name - as malarian death ravaged his colleagues; who advised a young naturalist before he set off on the Beagle for the Galapagos; who raised two sons as a widower and brought them, along with their British traditions, to the frontiers of Ontario and endured the bucolic days of a half-pay vice admiral, building a border town with his older brother. At the age of sixty-nine, Alexander Thomas Emeric Vidal had long outlived his siblings, his wife, and his eldest son, and collapsed in the care of strangers whose names were hidden from family lore.

This was perhaps a find for the history books, although they were already saturated by accomplished people, long forgotten. Memories are the first casualty of death, followed by flesh, then possessions. By the time those who knew the deceased are deceased themselves, the stonework begins to fade and all that is old and insignificant is washed away with the dust. A spirit is kept alive by those who make efforts to keep it alive.

I could only linger there so long. There was still much more work to do before I caught an evening train back to London. Besides, I was kneeling in a cemetery, muttering to a stone. So I set off for the BRO, determined to find out who was with ATEV during his final days. In less than twenty-four hours, I came to know that world – I now needed to know the people.